North and south

M. J. Driscoll

My title does not refer to Mrs Gaskell’s highly esteemed novel North and south (1854-55), in which the “dark satanic mills” of northern Britain are contrasted with the supposed refinements of the south, which I must confess I have never actually read. Rather, I refer to the way in which these two points of the compass are charged with meaning, it has always seemed to me, to a greater extent than are any of the others.[1]

Although I have not (yet) had the pleasure of reading North and south, I have read the odd book in my time. Two of my very favourites are books intended for children, but which I discovered first as an adult, when I read them for my own children. The first is an American book called Stuart Little, written by E. B. White (1899-1985) and published in 1945. White was a life-long resident of New York City and a contributing editor on The New Yorker, pieces from which he collected and published separately; the last such collection was entitled — interestingly from the point of view of the present article — The points of my compass. He also wrote, with Thurber, the book Is sex necessary?, and, always himself a brilliant stylist, produced a revised edition of William Strunk’s The elements of style, which I read early on in my career and benefited from greatly.[2]

The eponymous hero of Stuart Little is a mouse, born to a human family. Being mouse-sized, Stuart lives in a world of giants, but copes admirably. Midway through the book he meets the pretty songbird Margalo, who spends a few days in the Littles’ house, having been found nearly dead on the windowsill by Mrs Little and nursed back to health. It seems to Stuart that “he ha[s] never seen any creature so beautiful as this tiny bird”. Discovering that one of the neighbourhood cats plans to eat her, Margalo flies away without telling anyone, and the driving force of the remainder of the narrative is Stuart’s search for her, or, if you will, for the beauty of which he has been afforded a glimpse.[3]

At the end of the book Stuart meets a telephone linesman and asks if he has seen Margalo. He describes her for him and the linesman promises to get in touch if he does. Then the linesman asks Stuart in which direction he is headed, to which he replies that he is headed north. The linesman says that he has always enjoyed going north, although both south-west and east are also fine directions. He continues:

“There’s something about north,” he said, “something that sets it apart from all other directions. A person who is heading north is not making any mistake, in my opinion.”

“That’s the way I look at it,” said Stuart. “I rather expect that from now on I shall be traveling north until the end of my days.”

“Worse things than that could happen to a person,” said the repairman.

“Yes, I know,” answered Stuart.

“Following a broken telephone line north, I have come upon some wonderful places,” continued the repairman. “Swamps where cedars grow and turtles wait on logs but not for anything in particular; fields bordered by crooked fences broken by years of standing still; orchards so old they have forgotten where the farmhouse is. In the north I have eaten my lunch in pastures rank with ferns and junipers, all under fair skies with a wind blowing. My business has taken me into spruce woods on winter nights where the snow lay deep and soft, a perfect place for a carnival of rabbits. I have sat at peace on the freight platforms of railroad junctions in the north, in the warm hours and with the warm smells. I know fresh lakes in the north, undisturbed except by fish and hawk and, of course, by the Telephone Company, which has to follow its nose. I know all these places well. They are a long way from here — don’t forget that. And a person who is looking for something doesn’t travel very fast.”

“That’s perfectly true,” said Stuart. “Well, I guess I’d better be going. Thank you for your friendly remarks.”

“Not at all,” said the repairman. “I hope you find that bird.”

Stuart rose from the ditch, climbed into his car, and started up the road that led toward the north. The sun was just coming up over the hills on his right. As he peered ahead into the great land that stretched before him, the way seemed long. But the sky was bright, and he somehow felt he was headed in the right direction.

My second text today comes from an English children’s book, The wind in the willows by Kenneth Grahame (1859-1932). Apart from a number of essays and stories, dealing predominantly also with childhood, The wind in the willows, published in 1908, is Grahame’s only work. It began as stories and letters to his son, Alistair, from whose suicide while an undergraduate at Oxford Grahame never recovered.[4] For most readers, especially younger ones, the book is dominated by the ridiculous figure of Mr Toad,[5] but for me what The wind in the willows is “about” is the friendship between Ratty, who is a water rat,[6] and Mole, who is a mole.

Chapter IX is entitled “Wayfarers all”. It is late summer, and Ratty begins to notice the stirrings of the animals who are preparing to head south. He engages several swallows in conversation, asking them how they could ever leave “this pleasant place”. They tell him that he doesn’t understand about “the call of the South”, and he then asks them why, if the south is so wonderful, they ever bother to return, and they explain that there is “the other call [...] in its due season”.

Shortly thereafter he encounters a seafaring rat, who hails from the port of Constantinople, although as he says he is “a sort of a foreigner there too”, being descended from one of the rats that came with Sigurður Jórsalafari. He tells Ratty at length of his adventures on “classic seas whose every wave throbs with a deathless memory”, among the Grecian isles and the Levant, to Venice, “a fine city, wherein a rat can wander at his ease and take his pleasure! Or, when weary of wandering, can sit at the edge of the Grand Canal at night, feasting with his friends, when the air is full of music and the sky full of stars.” He has tried the life of the country, but has had enough and is now on his way to find a ship that will take him back to the south.

And you, you will come too, young brother; for the days pass, and never return, and the South still waits for you. Take the Adventure, heed the call, now ere the irrevocable moment passes! ‘Tis but a banging of the door behind you, a blithesome step forward, and you are out of the old life and into the new! Then some day, some day long hence, jog home here if you will, when the cup has been drained and the play has been played, and sit down by your quiet river with a store of goodly memories for company. You can easily overtake me on the road, for you are young, and I am ageing and go softly. I will linger, and look back; and at last I will surely see you coming, eager and light-hearted, with all the South in your face!

Mesmerised by the seafaring rat’s tales, Ratty does indeed try to follow, but is brought back to his senses by Mole.

Like Stuart, I have always looked north, and have somehow always felt that I was headed in the right direction; and I did succeed in finding my bird. But I have also always felt the pull of the south. I know that the recipient of this Festschrift, himself a bit of a wayfarer, will know of these different longings.

Notes

1. I admit that “east” and “west” are also fairly heavily laden with associations, as, I suppose, is a direction like “north by north-west”. (Back)

2. The first rule in The elements of style is: “Form the possessive singular of nouns with ’s. Follow this rule whatever the final consonant. Thus write, Charles’s friend [...].” (This was written well before all the business with that Parker-Bowles woman.) This is a common error in English, where one frequently encounters Charles’ or, even better, Charle’s. While I am aware that Danish is not English and therefore allowed to have rules of its own, however bizarre some of them may seem (why, for instance, is c retained before a front vowel, where it is pronounced like s, but changed to k before a back vowel, and what in heaven’s name is so wrong with the letter x that it was thought preferable to write ks?), I find that forms such as “Marx’ teori”, “Bush’ mangel på intelligens” or “Milosovic’ enorm brug af hårlak” always have me reaching for my red pen. (Back)

3. As some of my readers may be aware, Stuart Little is “now a major motion picture”, as the phrase goes, having been given the Hollywood treatment a year or two ago. I haven’t seen the film — intentionally — but I gather that the Margalo figure has been left out altogether, which is a bit like leaving the ghost out of Hamlet, or, indeed, making an action hero out of Romeo and skipping the soppy bits with Juliet. (Back)

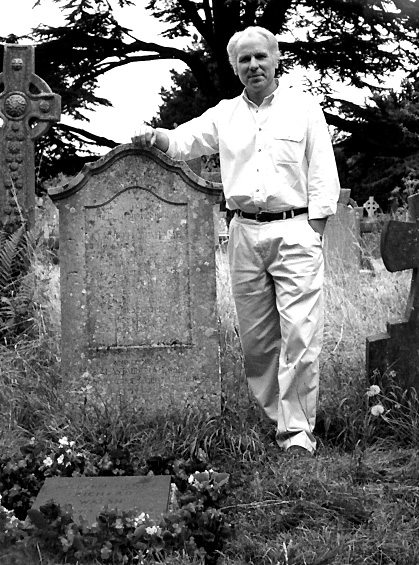

4. Grahame is buried in the graveyard of St Cross Church in Oxford, not a stone’s throw from the Turville-Petre Room in the English Faculty Library, where I spent several happy years; in fact I frequently had my lunch only a few feet from his grave. (Back)

4. Grahame is buried in the graveyard of St Cross Church in Oxford, not a stone’s throw from the Turville-Petre Room in the English Faculty Library, where I spent several happy years; in fact I frequently had my lunch only a few feet from his grave. (Back)

5. The wind in the willows was dramatised by A.A. Milne — the Winnie the Pooh man — as Toad of Toad Hall (1930) and became a frequently performed Christmas play. Just for the record, I should like to say that I am not a great fan of Winnie the Pooh, which always strikes me as precisely the sort of fatuous, simpering rubbish that gives children’s literature a bad name. Milne had some very canny things to say about his better’s work, however: “One does not argue about The Wind in the Willows. The young man gives it to the girl with whom he is in love, and, if she does not like it, asks her to return his letters. The older man tries it on his nephew, and alters his will accordingly. The book is a test of character. We can’t criticize it, because it is criticizing us. But I must give you one word of warning. When you sit down to it, don’t be so ridiculous as to suppose that you are sitting in judgment on my taste, or on the art of Kenneth Grahame. You are merely sitting in judgment on yourself. You may be worthy: I don’t know, but it is you who are on trial.” (Back)

6. Ratty, whose great passion is boats (“Believe me, my young friend, there is NOTHING — absolute nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats"), was apparently modelled on Frederick Furnivall (1825-1910), secretary of the Philological Society and founder of the Early English Text Society, who was a great fan of rowing, in particular in the company of healthy young women. He even founded a boatclub for women, one of the first in Britain, originally “Hammersmith Sculling Club For Girls”, now “Furnivall Sculling Club”, and frequently acted himself as cox. It must be noted that Ratty shares with Furnivall only his enthusiasm for messing about in boats; The wind in the willows is an entirely “sexless” book, there being no female characters to speak of in it, for which reason it has tended to be vilified by feminists, or at least by that school of feminist literary criticism which counts the number of female characters in a book and judges its importance accordingly. (Back)

© M. J. Driscoll This article first appeared in Arnarflug: rejselekture for Örn Ólafsson på hans 60-års fødselsdag, 4. april 2001 (Copenhagen, 2001).